Denmark is the least corrupt country in the world

Integrity in politics is key to fighting against corruption and here Denmark takes the lead once again. The higher rank is wastly due to Denmarks high degree of press freedom, access to information about public expenditure, stronger standards of integrity for public officials, and independent judicial systems:

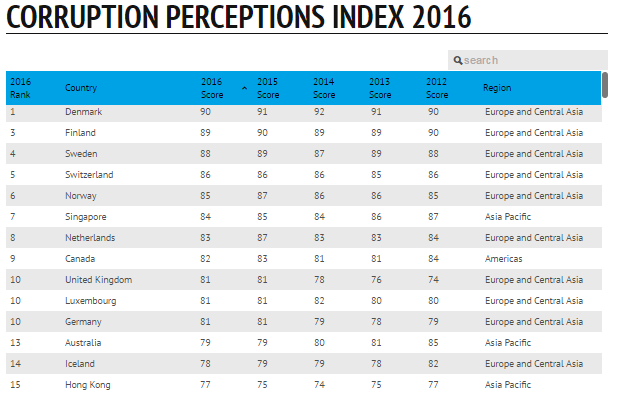

No country gets close to a perfect score in the Corruption Perceptions Index 2016.

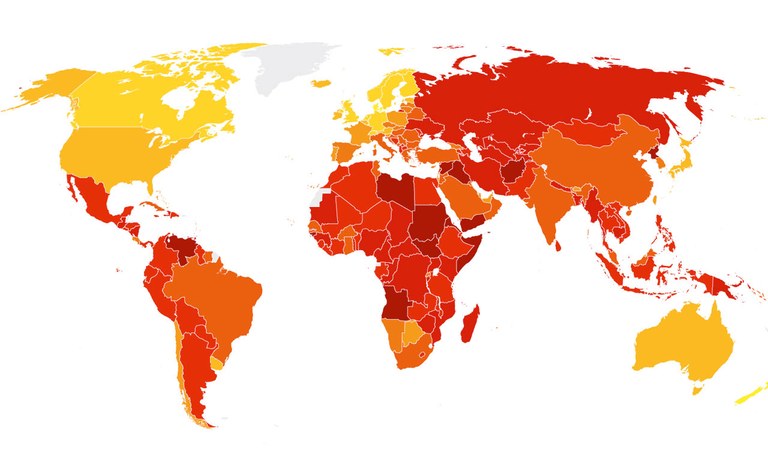

Over two-thirds of the 176 countries and territories in this year's index fall below the midpoint of our scale of 0 (highly corrupt) to 100 (very clean). The global average score is a paltry 43, indicating endemic corruption in a country's public sector. Top-scoring countries (yellow in the map below) are far outnumbered by orange and red countries where citizens face the tangible impact of corruption on a daily basis.

There are no drastic changes in Europe and Central Asia in the Corruption Perceptions Index 2016, with only a few exceptions. However, this does not mean that the region is immune from corruption. The stagnation does not indicate that the fight against corruption has improved, but quite the opposite.

High-profile scandals associated with corruption, misuse of public funds or unethical behaviour by politicians in recent years has contributed to public discontent and mistrust of the political system.

Ukraine shows a minor improvement by 2 points on this year’s index. This can be attributed to the launch of the e-declaration system that allows Ukrainians to see the assets of politicians and senior civil servants, including those of the president. However, cases of Grand Corruption against former president Yanukovych and his cronies are currently stalled due to systemic problems in the judicial system.

In many countries of the region, insufficient accountability has generated a perception of quasi-impunity of political elites, and the current wave of populism over Europe seems to enable legalisation of corruption and clientelism, feeding the extreme power of wealthy individuals that steer or own the decision making power.

Corruption scandals have also hit a number of EU countries. Last year in Denmark, the top country on the index, 20 members of the Danish Parliament (11 percent of 179 members) did not declare their outside activities or financial interests in their asset declarations. In the same year, Dutch members of the Police Works Council resigned following an investigation that revealed how a significant amount of the Council’s money was used to pay for expensive dinners, parties and hotels.

This is highly alarming. When core institutions in a democratic society – political parties, parliament, public administration and the judiciary – are systematically implicated with corruption, they cease to be regarded as responsive to people’s needs and problems.

Integrity in politics is key to fighting against corruption. In the Western Balkans, Transparency International’s recent report attributes weaknesses in law enforcement to captured political systems in which politicians wield enormous influence on all walks of public life, while being close to wealthy private businessmen or even organised crime networks.

Capture of political decision-making is one of the most pervasive and widespread forms of political corruption in the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) region, where a culture of impunity prevails among politicians, prosecutors and oligarchs. In many CIS, EU accession and Eastern European countries, it is common to have MPs or local governors who are also business owners, without being questioned by the public, which perceives this as something normal. Companies, networks and individuals unduly influence laws and institutions to shape policies, the legal environment and the wider economy to their own interests.

In this case having a comprehensive legal framework is not enough. What is required is effective implementation of anti-corruption provisions.

In countries where political decision-making is not captured, it is very important that governments assess risks in everyday decision making and administrative procedures, identifying possible gaps in order to act preventively, improve controls and to regain the trust and confidence of their citizens.

This year’s results highlight the connection between corruption and inequality, which feed off each other to create a vicious circle between corruption, unequal distribution of power in society, and unequal distribution of wealth.

– José Ugaz, Chair of Transparency International

The interplay of corruption and inequality also feeds populism. When traditional politicians fail to tackle corruption, people grow cynical. Increasingly, people are turning to populist leaders who promise to break the cycle of corruption and privilege. Yet this is likely to exacerbate – rather than resolve – the tensions that fed the populist surge in the first place. (Read moreabout the linkages between corruption, inequality and populism.)

More countries declined than improved in this year's results, showing the urgent need for committed action to thwart corruption.

PUTTING THE SCORES IN CONTEXT

The lower-ranked countries in our index are plagued by untrustworthy and badly functioning public institutions like the police and judiciary. Even where anti-corruption laws are on the books, in practice they're often skirted or ignored. People frequently face situations of bribery and extortion, rely on basic services that have been undermined by the misappropriation of funds, and confront official indifference when seeking redress from authorities that are on the take.

Grand corruption thrives in such settings. Cases like Petrobras and Odebrecht in Brazil or the saga of ex-President Viktor Yanukovych in Ukraine show how collusion between businesses and politicians siphons off billions of dollars in revenue from national economies, benefitting the few at the expense of the many. This kind of systemic grand corruption violates human rights, prevents sustainable development and fuels social exclusion.

Higher-ranked countries tend to have higher degrees of press freedom, access to information about public expenditure, stronger standards of integrity for public officials, and independent judicial systems. But high-scoring countries can't afford to be complacent, either. While the most obvious forms of corruption may not scar citizens' daily lives in all these places, the higher-ranked countries are not immune to closed-door deals, conflicts of interest, illicit finance, and patchy law enforcement that can distort public policy and exacerbate corruption at home and abroad.